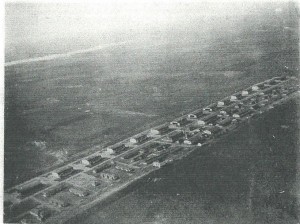

Used With Permission From The Wichita County Archive

Call Field was an aviation base in Wichita Falls, Texas during the Great War. The presence of Call Field provided a strong sense of community pride and identity for the residents of the city in the early twentieth century. Those feelings and attitudes are still present today. A multitude of planes, buildings and troops were necessary to make Call Field an operation base. Unfortunately, only one building still remains – the stable where the horses were kept. Additionally, a plane that was actually flown at Call Field is on display at the Wichita Falls Municipal Airport, located on the northeast side of Wichita Falls. It is accompanied by a beautiful mural which was painted by Ms. Ward, a local artist.

FUN FACT: The first pilot to land a plane in Call Field was a women….it was a crash landing.

The construction of Call Field began in the summer of 1917.[1] According to the Shepard Air Force Base historian, Dwight Tuttle, between “2,500 and 3,000 men were needed” to help build the airfield. Many of these workers were from North Texas. The city of Wichita Falls helped prepare the location for the airfield by filling “two small ponds on the grounds” and cutting “[t]rees…and fences.”[2] Utility lines, including water and electricity, were extended and paid for by the City of Wichita Falls. F. N. Lawton, a Chamber of Commerce member, noted “that the mains and pipes were all ordered [and] rushed through on government service.”[3]The airfield was designed to house “seventy-two airplanes” and was described by local papers as a “wonder.”[4] Citizens of Wichita Falls took pride in this airfield. Such enthusiasm is captured in a newspaper article which stated, “it is reasonably certain that if visitors [to Call Field] are allowed, there will be plenty of them.”[5] Community involvement helped establish the airfield. Joseph A. Kemp, a Chamber of Commerce member and entrepreneur, campaigned in Wichita Falls and Washington D.C. for the establishment of an aviation base. Kemp and Frank Kell privately donated $20,000 in total and convinced the chamber of commerce to donate an additional $35,000 for the construction of Call Field.[6] Based on his efforts in Washington D.C., Kemp secured the establishment of Call Field for a contracted lease of $1,137.77 with the option for the United State Government to purchase the land for $64,000.[7] Addressing the Wichita Falls Chamber of Commerce, Kemp “recommended a motion…that he [would] stand back of it financially and be responsible for what amount is necessary to land the Camp.”[8] One month later, “[t]hirty buildings [were] rooted, and the exterior[s] finished.”[9]Local “accommodating landladies” helped serve lunch to the workmen.[10] The article predicted that within the“[n]ext week, the two great additions to the camp will be roads and paint.”[11] Call Field’s construction progress was compared to that of a “chameleon – it changes its aspects every few minutes.”[12] Call Field’s establishment was unique. Never had the War Department “made any leases for aviation camps, and [therefore] had no precedent to follow.”[13] Future Aviation camps of North Texas, including Waco, were designed from the success of Call Field.

During Call Field’s establishment and operation, Wichita Falls experienced an historic drought. According to the Chamber of Commerce minutes, Washington D.C. sent correspondence “concerning [the] water supply at Call Field” which was regarded as “insufficient.” [14] Major Curtis Atkinson, Medical Officer of Call Field, stated that “there was a great water shortage” and that the “purity of the water” also caused concern.[15] Wichita Falls was “using an old fashioned method of purifying the water by chloride of lime.”[16] Major Atkinson regarded this method as unacceptable and threatened “to recommend to the medical department at Washington [to] change…the field” to a city with better water.[17] The Chamber of Commerce reacted by guaranteeing Call Field 125,000 “gallons of water per day” and “a chlorinating plant…for the field.”[18] The chlorinating device was estimated to cost the city $750.00.[19] However, Wichita Falls itself continued to suffer from a water shortage. In Washington D.C., Frank Kell “secured deposits of Government funds in banks in drought stricken parts of Texas.”[20]

The Chamber of Commerce again requested emergency aid in August of 1918. They appealed to the State of Texas for aid to the “extent of not less than Fifteen Million Dollars.”[21] In addition, the government was asked to authorize “an issuance of Ten Million Five percent State Bonds” to aid famers and ranchers of West Texas.[22] These drought conditions did not improve until January of 1919.[23]

Wichita Falls grew economically due to the airfield. Call Field’s regional presence cultivated business opportunities that had not previously existed. Entrepreneur Joseph A. Kemp attracted the M. K. and T railroad due to the airfield’s construction. Kemp announced that the railway undertook “to lay the whole of the required amount, without charge to the Chamber of Commerce.”[24] Kemp estimated that such an investment would have cost the city “close to fifteen thousand dollars.”[25] Financial institutions also benefited from the wartime activity. The National Bank of Commerce of Wichita Falls reported that since 1914, “the bank has increased its capital surplus and profit account to $130,000.00 with deposits of more than $750,000.00.”[26] These capital resources totaled to “be about $1,200,000.000.”[27] According to the U.S. Department of Labor inflation calculator, the financial power of the National Bank of Commerce, adjusted for modern inflation, would be worth an estimated $18,572,741.72.[28] Although this research cannot distinguish between the various possible funding sources of the bank’s financial expansion, the value of the bank’s capital assets showed that Wichita Falls was witnessing major economic growth. Debatably, this growth derived from wartime activities such as Call Field and its support industries. The oil boom, which later economically defined North Texas, would begin on July 26, 1918.[29]

Call Field initially served as an airfield but was later used as a training school for new pilots.[30] Personnel from various parts of the nation trained at this school. Service men originated “from California, New York, New Jersey…[and]… similarly distant parts.”[31] These men followed an innovative curriculum which included “ground and aerial gunnery, aerial reconnaissance and observation.”[32] Call Field helped pioneer the new field of aerial photography.[33] Photography had been attempted by taking “pictures from balloons, kites and even pigeons equipped with a miniature apparatus.”[34] Aerial photography was highly valued in trench warfare due to the “calm and keen perception and a perfect memory” that a photograph possesses in comparison to human observation.[35] The training course at Call Field was “designed to familiarize the pilot with the fundamentals of operating the aerial cameras over the enemy lines.”[36] Accuracy with both the camera and the gun were needed in order to be a successful aerial photographer. Students learned “to shoot the Hun down.”[37] The attached gun “can be synchronized so as to shoot through the propeller” so students “can get all of the actual experience necessary in the aerial gunnery” to combat enemy forces.[38]

Used With Permission From the Wichita County Archive

The pilots also dealt with frequent mechanical failures that plagued the newly pioneered planes. Such malfunctions caused the death of thirty-four pilots at Call Field.[39] Most monthly publications of the Call Field Engineer and later the Call Field Stabilizer featured memorial pages dedicated to young pilots who perished during training. Featured below is a photograph of a downed practice airplane.

After the Great War, Wichita Falls heavily campaigned to the War Department to keep Call Field as a permanent base. Senator Sheppard desired to have Call Field “retained as a permanent aviation camp.”[40] The Wichita Falls Chamber of Commerce “appointed Mr. Kemp…with Mr. Kell” to speak with U.S. Congress House Speaker Champ Clark and Senator Owens to lobby for Call Field to remain permanently. However, the December tenth meeting minutes of the Chamber of Commerce record Kemp stating that “it was unwise at this time to send a committee to Washington” and that he “had taken the matter up with Col. Edgar.”[41]Kemp’s reluctance remains a mystery.

Used With Permission From The Wichita County Archives

Wichita Falls had just recovered from the Spanish Flu epidemic. Possibly the influenza somehow influenced Kemp’s disinclination. However, Call Field’s deactivation was arguably inevitable. The Wichita Daily Times reported on November 24, 1918 that “forty-three of the eighty-eight officers…have asked for a complete discharge.” [42] The December issue of the Call Field Stabilizer was reported to be “well illustrated” in order to serve as an “interesting souvenir for the days to come, when perhaps there will be no more camp.”[43] Meanwhile service members were stated to have “made some investments in [the] oil companies operating” throughout North Texas. In conclusion Call Field had significantly defined the Wichita Falls Great War home front experience.

Citations

[1] Dwight W. Tuttle, Gary W. Boyd, George R. Fosty, Sustaining the Wings: A Fifty-Year History of Sheppard Air Force Base (1941 – 1991) [Wichita Falls: Midwestern State University Press, 1991], 2

[2] “Contract Awarded for Aviation Buildings Here,” Wichita Daily Times, 27 August 1917.

[3] Wichita Daily Times, 27 August 1917.

[4] “Many Buildings Required for Aviation Camp,” Wichita Daily Times, 26 August 1917.

[5] “Many Buildings Required for Aviation Camp,” Wichita Daily Times, 26 August 1917.

[6] Tuttle, 2.

[7] Chamber of Commerce, (Wichita Falls), Minutes of Meeting of the Chamber of Commerce, 23 August 1917, meeting of 23 August 1917.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Aviation Camp Building Program Being Pushed to Completion With Greater Speed Than Shown Before,” Wichita Daily Times, 28 September 1917.

[10] Wichita Daily Times, 28 September 1917.

[11] Wichita Daily Times, 28 September 1917. .

[12] Wichita Daily Times, 28 September 1917.

[13] “Contract Awarded for Aviation Buildings Here,” Wichita Daily Times, 27 August 1917.

[14] Chamber of Commerce, (Wichita Falls), Minutes of Meeting of the Chamber of Commerce, 21 January 1918, meeting of 21 January 1918.

[15] U.S. Library Of Congress, “Dr. Curtis Atkinson,” http://lcweb2.loc.gov/mss/wpalh3/33/3309/33090105/33090105.pdf (accessed March 27, 2015).

[16] Ibid.,

[17] Ibid.,

[18] Chamber of Commerce, (Wichita Falls), Minutes of Meeting of the Chamber of Commerce, 5 March 1919, meeting of 5 March 1919.

[19] Ibid.,

[20]Chamber of Commerce, (Wichita Falls), Minutes of Meeting of the Chamber of Commerce, 12 February 1918, meeting of 12 February 1918.

[21]Chamber of Commerce, (Wichita Falls), Minutes of Meeting of the Chamber of Commerce, 27 August 1918, meeting of 27 August 1918.

[22]Ibid.,

[23] National Weather Service Weather Forecast Center: Norman Oklahoma, “Daily Historical Weather Information for the Entire Year,” National Weather Service,http://www.srh.noaa.gov/oun/wxhistory/gethistory.php?month=all&day=all (accessed 30 March 2015).

[24] “Katy Will Lay Tracks to Site Aviation Camp,” Wichita Daily Times, 17 August 1917.

[25] Wichita Daily Times, 17 August 1917.

[26] “National Bank of Commerce” (26 May 1918), Wichita Falls, advertisement [from Wichita Daily Times (Wichita Falls: Wichita Daily Times, 26 May 1918)].

[27] “National Bank of Commerce,” 26 May 1918.

[28] United State Department Of Labor . “BLS Inflation Calculator,” Bureau Of Labor Statistics, http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl?cost1=1200000&year1=1918&year2=2015 (accessed 4 March 2015).

[29]“ S.L. Fowler Tells of the Organization of Company And Gives Wife the Credit,” Wichita Daily Times, 19 January 1919.

[30] Tuttle, 3.

[31] “Home Sickness Worst Ailment at Call Field,” Wichita Daily Times, 27 January 1918.

[32] Tuttle, 3.

[33] Clint Leland Smith, “A History of Call Aviation Field” (MA Thesis., Midwestern State University, 1970), 85.

[34] Engineering Department of the U.S Aviation School at Call Field, The Call Field Engineer, Wichita Falls, Texas (15 August 1918): 12.

[35] Ibid., 13.

[36] Engineering Department of the U.S Aviation School at Call Field, The Call Field Engineer, Wichita Falls, Texas (15 July 1918): 20.

[37] “Aerial Gunnery Practice Starts at Camp At Once,” Wichita Daily Times, 26 May 1918.

[38] Wichita Daily Times, 26 May 1918.

[39] Tuttle, 3.

[40] Chamber of Commerce, (Wichita Falls), Minutes of Meeting of the Chamber of Commerce, 3 December 1918, meeting of 3 December 1918.

[41] Chamber of Commerce, (Wichita Falls), Minutes of Meeting of the Chamber of Commerce, 10 December 1918, Meeting of 10 December 1918.

[42] “Some Officers At Call Field To Be Released,” Wichita Daily Times, 24 November 1918.

[43]“Stabilizer For December To Be Well Illustrated,” Wichita Daily Times, 1 December 1918.